The Conjure Book

The Conjure Book Servant of Birds

Servant of Birds The Eagle and the Sword (The Perilous Order of Camelot Book 2)

The Eagle and the Sword (The Perilous Order of Camelot Book 2) Wyvern

Wyvern The Last Legends of Earth

The Last Legends of Earth The Dark Shore (The Dominions of Irth Book 1)

The Dark Shore (The Dominions of Irth Book 1) Octoberland (The Dominions of Irth Book 3)

Octoberland (The Dominions of Irth Book 3) Arc of the Dream

Arc of the Dream p1b6fn7sdh1ln0g4v1pkvkuqim54

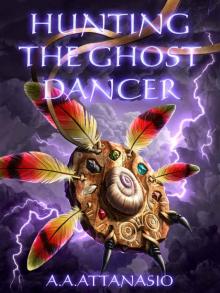

p1b6fn7sdh1ln0g4v1pkvkuqim54 Hunting the Ghost Dancer

Hunting the Ghost Dancer The Wolf and the Crown (The Perilous Order of Camelot Book 3)

The Wolf and the Crown (The Perilous Order of Camelot Book 3)